Python is a highly versatile and interpreted, high-level, general-purpose programming language. It was created by Guido van Rossum and first released in 1991. Python’s design philosophy emphasizes code readability and ease of use. Since then, Python has grown in popularity and is an excellent choice in scripting and rapid application development.

A lot of legacy applications are still written in Python 2. Companies facing a migration to Python 3 requires knowledge of the differences in both syntax and behavior. The purpose of this article is to outline the differences between Python 2 and Python 3. With examples, you will see how functions look syntacally the same in one version but behave completely different in another version.

Most Used Python Version

The newest version of Python is 3.7 was released in 2018. The next version 3.8 is currently in development and will be released in 2024. Although Python 2.7 is still widely used. Python 3 adoption is growing quickly. In 2016, 71.9% of projects used Python 2.7, but by 2017, it had fallen to 63.7%.

What Version Should I Use?

Depending on what your needs are and what you want done, choose the version that will help you the most. If you can do exactly what you want with Python 3.x then great! There are however, a few downsides such as:

- Slightly worse library support

- Some current Linux distributions and Macs still use 2.x as default

As long as Python 3.x is installed on your users’ computers (which in most cases are because most people reading this are developing something for themselves or on an environment they control) and you are writing things where you know none of the Python 2.x modules are needed, it is an excellent choice. Also most Linux distributions already have Python 3.x installed and nearly all have it available for end users. One caveat may be if Red Hat Enterprise Linux (through version 7) where Python 3 does exist in the EPEL repository, but some users may not be allowed to install anything from add-on locations or unsecured locations. Also some distributions are phasing Python 2 out as their former default install.

Instructors should be introducing Python 3 to new programmers, but discussing the differences in Python 2.

Refrain from starting any new development in Python 2 because as of January 2020, Python 2 will be EOL (“End of Life”) meaning all official support will cease.

What is the Difference Between Python 2 and 3?

The main difference is that some things will need to be imported from different places in order to handle the fact that they have different names in Python 2 and Python 3. Accordingly, the six compatibility package is a key utility for supporting Python 2 and Python 3 in a single code base.

We will discuss the major differences in each section of this article and provide examples of console screenshots in both Python 2 and Python 3.

Libraries: Python 2 vs Python 3

From a library standpoint, the libraries are hugely different in Python 2 vs Python 3. Many libraries developed for Python 2 are not compatible in Python 3. The developers of libraries used in Python 3 has good standards and have enhanced the Machine Learning and Deep Learning libraries.

Integer Division in Python 2 and 3

Integer division is the division of two numbers less the fractional part. In Python 2, you get exactly what integer division was defined to do.

Example 1. Integer Division in Python 2.

In the console screenshot below, you see the division of two integers. The result in Python 2 is also an integer. The fractional part is missing.

Example 2. Integer Division in Python 3.

In the console screenshot below, you see the division of two integers in Python 3. The result is a floating point number that includes the fractional part that is missing in Python 2.

If the fractional part is required in Python 2, you can specify one of the integers that you are dividing as a floating point number. That way, it forces the result to be a floating point number.

Print Statement Syntaxes Python 2 vs 3

In Python 2, print is a statement that takes a number of arguments. It prints the arguments with a space in between. In Python 3, print is a function that also takes a number of arguments.

Example 3. Print Statement in Python 2

In this example, we use the print statement with three arguments. Notice that Python 2 prints the three arguments separated by a space. Next, we use the print statement with round brackets surrounding the three arguments. The result is a tuple of three elements.

Example 4. Print Function in Python 3.

In this example, we use the print function with three arguments and we get the same result as in Example 3 with Python 2. However when we want to print the tuple, we have to surround the tuple with another set of rounded brackets.

To get the same result in Python 2 as Python 3, we can use the future directive to direct the compiler to use a feature that is available in a future release.

Example 5. Future Directive in Python 2.

Unicode Support in Python 2 vs Python 3

In Python 2 when you open a text file, the open() function returns a ASCII text string. In Python 3, the same function open() returns a unicode string. Unicode strings are more versatile than ASCII strings. When it comes to storage, you have to add a “u” if you want to store ASCII strings as Unicode in Python 2.

Example 6. Strings in Python 2

Example 7. Strings in Python 3.

In Python 2, there are two different kinds of objects that can be used to represent a string. These are ‘str’ and ‘unicode’. Instances of ‘str’ are byte representations whereas with unicode, are 16 or 32-bit integers. Unicode strings can be converted to byte strings with the encode() function.

In Python 3, there are also two different kinds of objects that can be used to represent a string. These are ‘str’ and ‘bytes’. The ‘str’ corresponds to the ‘unicode’ type in Python 2. You can declare a variable as ‘str’ and store a string in it without prepending it with a ‘u’ because it is default now. ‘Bytes’ corresponds to the ‘str’ type in Python 2. It is a binary serialization format represented by a sequence of 8-bits integers that is great for sending it across the internet or for storing on the filesystem.

Error Handling Python 2 vs Python 3

Error handling in Python consists of raising exceptions and providing exception handlers. The difference in Python 2 vs Python 3 are mainly syntactical. Let’s look at a few examples.

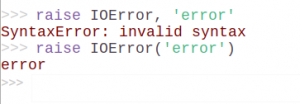

Example 8. Raise errors in Python 2.

In the console screenshot below, we try to raise error in both formats and it works.

Example 9. Raise errors in Python 3.

In the console screenshot below, raising error does not work in Python 3 as it was in Python 2.

With exception handlers, the syntax has changed slightly in Python 3.

Example 10. Try and Exception block in Python 2.

In the console screenshot below, we specify a try block with an exception handler. We purposely cause an error by specifying an undefined name in the ‘try’.

Example 11. Try and Exception block in Python 3.

In the console screenshot below, we specify the same code as the previous example in Python 2. Notice the new syntax in Python 3, requiring us to use the word ‘as’.

Comparing Unorderable Types

In Python 2, it was possible to compare unorderable types such as a list with a string.

Example 12. Comparing a list to a string.

Example 13. Comparing a list to a string in Python 3.

New in Python 3, a TypeError is raised if you try to compare a list with a string.

XRange in Python 2 vs Python 3

In Python 2, there is the range() function and the xrange() function. The range() function will return a list of numbers whereas the xrange() function will return an object.

In Python 3, there is only the range() function and no xrange() function. The reason why there is no xrange() function is because the range() function behaves like the xrange() function in Python 2. In other words, the range() function returns the range object.

Example 14. The Range() and XRange() function in Python 2.

In the console screenshot below, we see that the range() function returns a list containing 5 elements because we passed ‘5’ as an argument. When we use xrange(), we get an object back instead.

Example 15. The Range() function in Python 3.

As you can see from the console screenshot below, entering the range() function with ‘5’ as an argument causes an object to be returned. However when we try to use the xrange() function, we see that Python 3 does not like it because it is undefined.

In Python 2, there were a number of functions that return lists. In Python 3, a change was made to return iterable objects instead of lists. This includes the following functions:

- zip()

- map()

- filter()

- Dictionary’s .key() method

- Dictionary’s .values() method

- Dictionary’s .items() method

Future Module in Python 2 vs 3

If you’re planning Python 3 support for your Python 2 code then you might want to add the __future__ module. For example, integer division had changed from Python 2 to 3 but if you want your Python 2 code to behave like Python 3, all you have to do is to add this line:

“from __future__ import division”

Now in your Python 2 code, dividing two integers will result in a floating point number.

Example 16. Importing from the __future__ module.

As you can see below, when we divide 2 / 3, we get 0 which is type integer. But after we import division from the __future__ module, 2 / 3 returned type floating point number.

There are other things you can specify to make your future migrations easier. They include:

- Generators

- Division

- Absolute_import

- With_statement

- Print_function

- Unicode_literals

Recommended Python Training

Course: Python 3 For Beginners

Over 15 hours of video content with guided instruction for beginners. Learn how to create real world applications and master the basics.